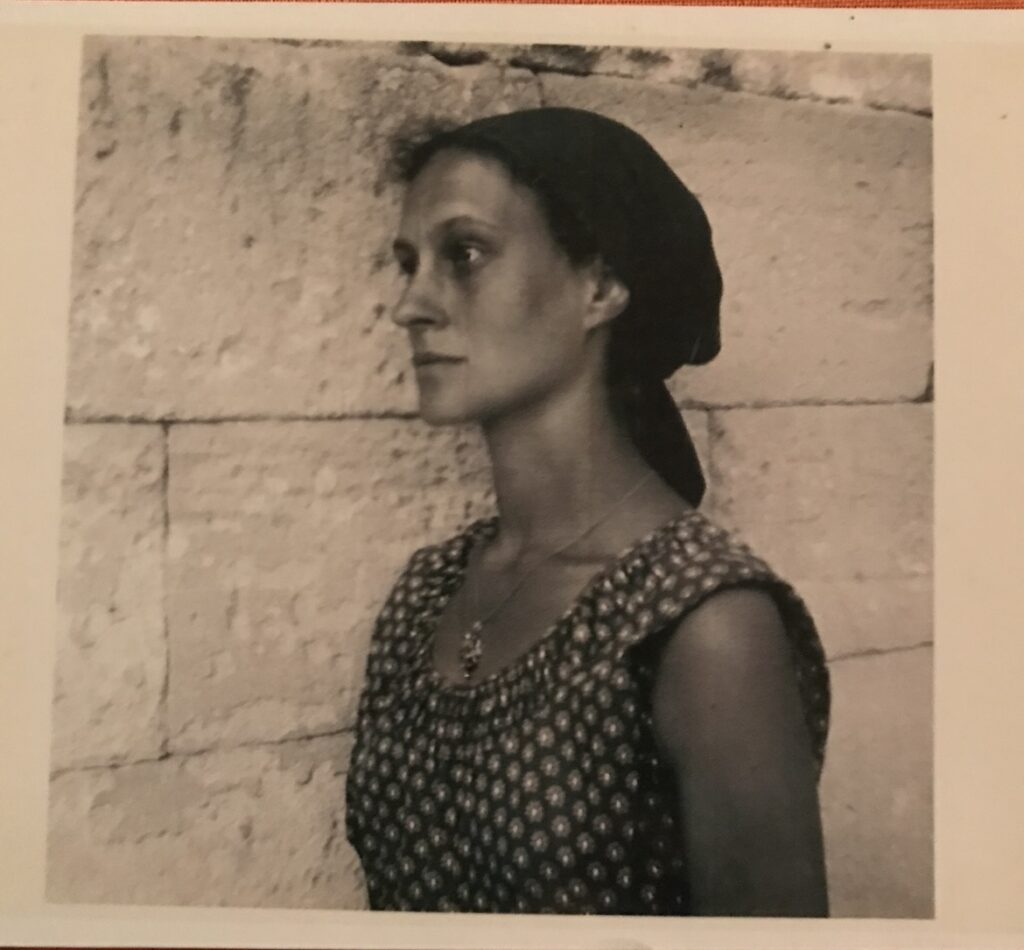

Anya Berger in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Katya Berger.

Anya Berger (1923–2018) is best known as the wife and “muse” of art critic and novelist John Berger. In 2018, after John and Anya Berger died, their daughter Katya Berger was with John’s archivist and biographer, Tom Overton, when they discovered paper records in the family basement. This suggests that works published in John’s name during their relationship, from 1958 to 1973—Picasso’s Successes and Failures, How to View, G.And A Lucky Man: The Story of a Country Doctor-Can considered a joint project. The family’s private archives document a period largely missing from John Berger’s main archive at the British Library.

Née Zisserman, Anya Berger was born in Manchuria to a Russian noble father and a Viennese Lutheran mother, who was considered Jewish by the Nazis. He came to England as a refugee in his teens, first on a scholarship to St. Mary’s boarding school. Paul, and then to read modern languages at St. Paul. Hugh’s College, Oxford. He was a polyglot, responsible for shaping the English-speaking left with his translations of Marx, Lenin, the fallen Freudian Wilhelm Reich, and the architect Le Corbusier.

The collaborative nature of her relationship with John was no secret; they once signed a telegram “jonanya.” Although Anya was a linguist, they collaborated “officially” on several translations, the most famous being the works of Aimé Césaire. Return to my native land (1939, translation 1970). Method See (1972), the TV show and subsequent book that made John Berger famous, drew heavily on Walter Benjamin’s writings on art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Anya, a fluent German speaker, had introduced Benjamin’s ideas to her husband before Arendt-Zorn’s translation Illumination published in English in 1968.

Anya Berger appears in the second episode How to Viewon “Women and the Arts.” The show presented the concept of the male gaze to mainstream audiences a year before Laura Mulvey wrote her canonical essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” As part of the group of women tasked with responding to naked women, Anya was the first to speak, sitting opposite her husband, leaning forward firmly on her wide knees. “Of course, we have an image of ourselves, and it is a visual image, but I wonder how much European classical painting has shaped that image.” He was excited.

“When I look at the paintings you show in your films, I can’t take them seriously, I can’t identify with them because they are always exaggerated, they attach themselves to some kind of secondary sexual characteristics, big breasts and big bee-stinging buttocks. [John Berger’s laughter]great things like that, and they are not real… Almost all the paintings you show are what are called ideal, and therefore they seem to me very unreal with respect to the deepest image I might have of myself, and with respect to the deepest pleasure I might feel in looking at another woman’s body.”

Anya Berger advances and complicates the show’s narrative arc. Its frame of reference is centuries-long, spanning not only decades and cities, but also eras and continents. However his name only appears on screen during the closing credits for less than five seconds. John and Anya almost broke up by the time the book from the show was published. It has become one of the most widely read art books, with sales in the UK alone reaching 1.5 million. Failed to register the contribution.

There is a degree to which she conceptualizes her role as muse: her daughter, Katya, thinks “mentor” is more appropriate. He sees himself participating in the creative work of his lover, and the people in his network, both as inspiration and as interlocutors, who shape the work from within. “I would like to take part in creative life,” he said to his granddaughter, Sonia Lambert, “but I know that I am not a creative artist myself, I do not have the necessary means. I am happy to take part in it.” However, one of the things that started to upset Anya after her split from John was the feeling that she had been exploited as part of their collaborative creative relationship.

In the summer of 1969, John Berger attempted to open their marriage to another woman, Annar Cassam. He is writing a novel G.a book about the gradual politicization of Don Juan in Europe before the First World War: it went on to win the Booker Prize the same year that How to View first broadcast. The novel is dedicated to his wife and fellow feminists: “To Anya/ and to her sisters in Women’s Liberation.”

He became increasingly uncomfortable with his wife’s influence on his writing. Katya told me how her mother’s support of her father’s work became so important that her father felt pressured and constrained. It is important to note that his next regular partner, Beverly Bancroft, with a background in the publishing business, was more concerned with licensing and rights than the content of her work, more agent than collaborator. Anya wasn’t sure about John’s vision for it Into Their Work trilogy, a project that ultimately took over ten years to complete, and tried to persuade him to devote his energies elsewhere.

Katya also remembered the different attitudes towards each of her parents’ literary works in their home. John Berger’s writing time is sacred, and everyone in the house must be silent. In contrast, Anya Berger writes only after her many tasks are completed, moments announced by the clicks and dings of a typewriter. It is perhaps significant that most of his unpublished archives are fragmentary, or take the form of diary entries, which withstood much of the intrusion of domestic routine.

Papers in the family’s personal archives document a period of enormous creative productivity for Anya Berger around the time of their separation, fueled by a kind of bruised exuberance. Some of this writing found an official outlet: an article entitled “Women of Algiers” for New Left Review in 1974, and an article entitled “in the shit no more” for a groundbreaking British feminist publication Spare ribs in 1976. The latter is referred to on its contents page as “The story of a lone woman and a broken toilet seat”. He tells the hilarious story of his attempt to replace a malfunctioning toilet seat when his two children were home sick, his fingers covered in feces, and the joy that came from his success: “My duel with the toilet seat was the closest I got to pure sport in 51 years. My own personal Olympics.”

There remains a treasure trove of Anya Berger’s unpublished life writing: journal entries, memoirs, poems, letters, telegrams, doodles, short stories. Katya drew my attention to how the works were revised, corrected, and largely dated and organized; his mother had archived the work carefully, as if it were intended for readers, perhaps for publication. In an untitled fragment taken in the summer of 1974, after her separation from John, she begins: “To live alone is, first and foremost, to be invisible. There are no interested eyes watching you. You project no image. Except yourself.” This develops, over the course of two pages, into a reflection on her struggle with writing, to find a new way to see herself and be seen: “Then a thought occurred to me that seemed more interesting than the previous one. I toyed with it for a while and was prepared to let it go like its predecessor. But it occurred to me that, perhaps for the first time in my life, I was free to think it through—if not to the end, at least more deeply. That seemed to be what I wanted to do.”

Anya Berger’s writing practice then stalled for decades. However, near his death in 2016, as he drifted in and out of consciousness, speaking to his children in French and English, he provided outlines of the stories swirling in his head, fictionalized versions of the people he met, and the sights he witnessed. Some are taken from his personal conversations with Katya, about romantic failures and successes, disappointments and hopes. “I’m writing a new book in my head,” he tells his daughter, “It’s about Katya, an old woman who was pushed into the sea by her lover.” For Anya Berger, things that did not happen in her life carry the power of an event.

I collaborated with Katya Berger and feminist writer Mona Chollet to publish a two-volume collection of Anya Berger’s life writings. That fragment Paris Review is publishing, “New Optic,” written in 1969. It is a personal essay about sight and aging, but it touches on a subject, seeing and being seen, that was never far from his mind. “A new way of seeing,” wrote Anya, “suddenly it became the normal, old way—enough tolerable until then—becomes abnormal and even impossible.” Here, three years before John’s TV show airs, he anticipates—gives it?—its title.

Emily Foister researches, writes, and teaches about feminism and women’s work, with a focus on precarious archives.

News

Berita Teknologi

Berita Olahraga

Sports news

sports

Motivation

football prediction

technology

Berita Technologi

Berita Terkini

Tempat Wisata

News Flash

Football

Gaming

Game News

Gamers

Jasa Artikel

Jasa Backlink

Agen234

Agen234

Agen234

Resep

Download Film

Gaming center adalah sebuah tempat atau fasilitas yang menyediakan berbagai perangkat dan layanan untuk bermain video game, baik di PC, konsol, maupun mesin arcade. Gaming center ini bisa dikunjungi oleh siapa saja yang ingin bermain game secara individu atau bersama teman-teman. Beberapa gaming center juga sering digunakan sebagai lokasi turnamen game atau esports.