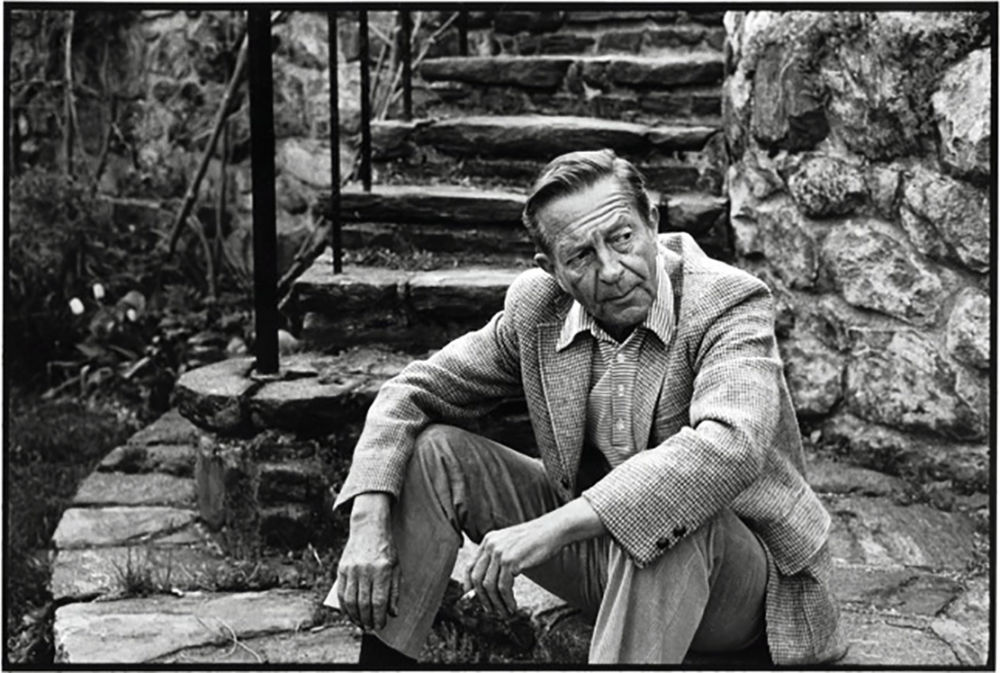

William F. Buckley Jr., 1954. Los Angeles Daily News. CC BY 4.0. via Wikimedia Commons

Of all the writers whose interviews have appeared in The Paris Review since its founding in 1953, none may be quite so aberrant as William F. Buckley Jr., subject of The Art of Fiction No. 146. Buckley’s interview appeared in the Summer 1996 issue, alongside one with the poet A. R. Ammons and fiction by Jonathan Franzen and Carolyn Cooke. It was curious company for the preeminent political journalist of the American right—the paterfamilias, even, of the whole postwar conservative movement.

It is not Buckley’s politics that makes his inclusion in the Writers at Work interview series surprising; right-wingers before him had made it into the magazine. The old Tory Evelyn Waugh, in his Art of Fiction interview, even declared that “an artist must be a reactionary.” No, what makes Buckley stand out in The Paris Review is that he was being interviewed about the art of fiction, not punditry.

The eleven spy novels Buckley produced between 1976 and 2005 were, essentially, his side gig—his Chablis money. He wrote them in the Swiss Alps while on vacation from editing the magazine he had started in 1955, National Review. The books’ hero is Blackford Oakes, a Bond-like agent of the Central Intelligence Agency. Small wonder: Buckley himself had briefly worked for the CIA in the late forties in Mexico, where his supervisor was the future Watergate burglar E. Howard Hunt. Oakes’s Cold War escapades are a fanciful version of the life his creator might have led had he stayed on in “the Company” instead of becoming a high-flying magazine editor and television show host. (Hunt, incidentally, went on to write more than fifty spy thrillers and was never interviewed in The Paris Review.)

“I found myself attracted to this idea of exploring historical data and visiting my own imagination on them,” he told his interviewer, the publisher Sam Vaughan. “The very successful book on the death of Kennedy written by Don DeLillo, Libra, does, of course, that …” The Blackford Oakes novels had their highbrow admirers—Vladimir Nabokov raved about the first one, Saving the Queen (1976)—but critical consensus held Buckley at some distance from John le Carré and Frederick Forsyth (his most immediate influence), never mind DeLillo. The problem with Blackford Oakes, wrote Ken Follett in the London Review of Books, is that his inner life was kept so hidden from the reader. In Oakes “there is no sympathetic magic—a problem not uncommon among journalists who turn to fiction.” Still, Blackford Oakes became a fixture on the bestseller lists.

It was in writing about his own life, though, that Buckley came closest to literary insight. Years before Blackford Oakes, he decided that the typical waking hours of William F. Buckley Jr. contained material enough for a work of intrigue. The most distinctive books he ever wrote are Cruising Speed (1971) and Overdrive (1983), diary-like experiments in what he called “personal documentary.” Sam Tanenhaus, whose thousand-page Buckley: The Life and Revolution That Changed America was published last summer, describes them as “nonbooks.” Buckley was a master of the nonbook, “at once dashed off and padded out.” His variations on it include assemblages of columns, press releases, and other editorial bits and bobs, like God and Man at Yale (1951) and The Unmaking of a Mayor (1966), while “personal documentary” was more like “a pieced-together montage,” Tanenhaus writes, “cinema verité rather than a straightforward narrative, with Buckley holding the camera and pointing it at himself.”

Cruising Speed and Overdrive each chronicle a single week in Buckley’s working life: writing columns, editing NR, corresponding, lecturing, luncheoning, schmoozing. Buckley spent his days in seeming hyperactivity, advancing the conservative cause by any genteel means necessary while satisfying an abject need for social and intellectual stimulation.

“The car pulls in at ten,” reads the first sentence of Cruising Speed, on the morning of Monday, November 30, 1970,

and my wife, Pat, undertakes to supervise the loading of it. This is an operation, because it has been a long weekend, during which a lot of clutter accumulates that we’ll need in New York, and there is the fruit and the cheese and the flowers that would spoil if we left them in Stamford until the weekend. Angela, the maid, will go with us … and three dogs …

One thinks of Woolf’s Clarissa, resolved to “buy the flowers herself” at the start of her own day of excitement, and of Lucy, Mrs. Dalloway’s maid, who has “her work cut out for her” by the second sentence of that novel.

So Buckley sets off floating on a cloud through the week’s business. A million things happen, few of them significant. Glittering invitations are received and others sent, and “names are dropped with a gilded clatter,” as Louis Menand put it recently in The New Yorker. There is a long passage in Overdrive on the subject of peanut butter (“My addiction is lifelong, and total”), and that is exactly what’s on offer here: straight from the jar, rich, but not quite a meal. These are not books of ideas but of errands.

When Buckley died in 2008, more than one of his obituarists noted that he never wrote the great political treatise—the big book—he might have. Such a book would have been about the ideology catalyzed by NR that was called fusionism: the blend of libertarian economics, repressive social conservatism, and anticommunist foreign policy that triumphed in the Reagan-Bush years. Instead, in Cruising Speed and Overdrive, Buckley delineates another kind of fusion, this one between intellectual entrepreneurship and intellectual celebrity, business and pleasure fully entwined.

For Buckley was also a brand. In addition to his work as an editor and columnist, he was a television personality, a third-party candidate for mayor of New York City, a sailor, a bon vivant, a character. (His Paris Review interview contains references to no fewer than three harpsichords in his possession.) This was not pure self-delusion. “You are charming and you’re very polite,” Huey P. Newton conceded, teasingly, during a 1973 taping of Firing Line.

Not everyone agreed with the Black Panther chairman, though. “He is so sublimely unself-conscious, so ‘blasphemously happy’ with his own life,” John Gregory Dunne wrote a decade later about Overdrive, “that he wishes to share with his readers what amounts to a 50,000-word advertisement for himself.” And yet plenty of people bought it. The Blackford Oakes novels sold better, but Buckley’s nonbooks proved to be his ticket to belletrist prestige. The editor William Shawn published excerpts of Cruising Speed in The New Yorker and even serialized Overdrive in its entirety. These and other contributions to The New Yorker, says Tanenhaus, were Buckley’s “proudest achievements as a writer.” The approval of one corner of the liberal media, at least, counted for something.

***

On the Saturday night of Cruising Speed, Buckley and his wife, the divine Pat, dine at a place called La Seine with Truman Capote, a friend, along with Capote’s editor Joe Fox and Lally Weymouth, the twenty-seven-year-old daughter of Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham.

Afterward, Capote insists they all go to the Sanctuary, a disco in a converted church in Hell’s Kitchen. This place has everything, Buckley reports: “psychedelic lights, blaring music, the dance floor crowded with homosexuals and lesbians and heteros, in ratio about 25-25-50, who dance with detached expression.”

There, suspending his distaste for the counterculture, Buckley is more curious than hostile. In fact he almost digs it:

We are very nearly alone in ordering our whiskeys-and-sodas: everyone else seems to be drinking Cokes, or nothing at all. I suppose that they are also smoking pot, though I am not good at detecting the smell of it … I find the rock [music] working through to me … the music—the sound—is sovereign, and you do not talk; you dance or sit; and there is Truman sitting, his glasses occasionally refracting the light, his expression resigned, his face reposed, while the bodies, many of them of black and beautiful, writhe, the faces always silent, resisting the inordinate, orgiastic demands of the sound …

A contact high? The recollection yields what was certainly an abnormal compliment to the beauty of blackness, to put it one way; a conspicuous amount of Buckley’s intellectual “work” in Cruising Speed consists of debating and dismissing the political claims of Black Americans, a lifelong vocation. The Sanctuary, moreover, was a gay establishment. The frisson it inspired in him is notable, if not because of the lasting speculation about his own sexuality, then for its salutary effect on his creativity.

In his Paris Review interview, Buckley recalls a conversation in Buenos Aires with Jorge Luis Borges, who was then blind. “Sometimes I think that beauty is not something rare,” Borges told him.

I think beauty is happening all the time. Art is happening all the time. At some conversation a man may say a very fine thing, not being aware of it. I am hearing fine sentences all the time from the man in the street, for example. From anybody.

For all that he revered Borges (himself no bleeding heart), Buckley was not a democratic listener in this way. So it is probably no coincidence that the polychromatic overload of the Sanctuary was the exact moment, he writes, when “the idea comes to me to write this journal of a week’s activity.” The result was of a piece with the New Journalism of people like Capote, Norman Mailer (author of Advertisements for Myself), and Joan Didion, whose talent Buckley encouraged early on.

Much conversation around Buckley’s legacy today revolves around his responsibility, or lack thereof, for the style of conservatism that gave us Donald Trump. The historian Jennifer Burns is right to identify a related inheritance that is especially evident in Cruising Speed and Overdrive: Buckley the proto-influencer.

Buckley wagered that if you were glamorous and interesting enough, there existed an audience of people for whom no detail of your daily life would be too trivial, no degree of disclosure so tedious as to outweigh the vicarious thrill of another person’s routine. Blackford Oakes was a fantasy character, but so was Buckley, in the “curated” manner of internet personalities today.

It could be a testament to Buckley’s influence, or at least to his prescience, that the breathless, rather bloodless style of these pages—their attention to surfaces and the minutiae of the high life—seems so familiar. But from where?

Take this passage, from another night out in Manhattan:

Now the Shirelles are coming out of the speakers, “Dancing in the Street,” and the sound system plus the acoustics, because of the restaurant’s high ceiling, are so loud that we have to practically scream out our order to the hardbody waitress—who is wearing a bicolored suit of wool grain with passementerie trim … The air conditioning in the restaurant is on full blast and I’m beginning to feel bad that I’m not wearing the new Versace pullover I bought last week at Bergdorf’s.

Of course this isn’t Buckley—it’s Bateman, from Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. But you can see how easily “personal documentary” lent itself to parody, and how unsettlingly its solipsism could read, if taken to the extreme.

***

Reading his Paris Review interview, you sense that Buckley was more keen to discuss fiction than most people were to ask him about it. (It’s probably telling that Vaughan, Buckley’s interviewer, was his own publisher and personal friend.) Writing novels brought Buckley immense satisfaction, it’s clear—though probably writing 1,500 words a day of anything feels good if you’re doing it at your place in Switzerland and a personal chef brings you a kir fifteen minutes before quitting time. Asked by Vaughan what his venture into fiction had meant to him, Buckley replied that novel-writing allowed him to locate “reserves of creative energy that I was simply unaware of.”

There could be no greater thrill to Buckley than discovering and exploiting such reserves. In secret, his craving for energy was pharmaceutical: Christopher Buckley has written sensitively and unguardedly of his father’s reliance on Ritalin, “which he used as a stimulant,” and Tanenhaus notes that Buckley’s prescription for it began as early as 1958. It might be wrong to make too much of this, but once you know about the Ritalin, it’s impossible to read Cruising Speed and Overdrive—not even their titles—in quite the same way. Perhaps they should be understood as pill books as much as nonbooks, to be shelved alongside Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Junky in the venerable American literature of drug-taking.

“Nothing would drive me battier than to do just a novel over the course of an entire month,” Buckley told The Paris Review. “I have only x ergs of purely creative energy, and when I’m out of those, what in the hell do I do then?” It was this restlessness that allowed him to sustain a satisfying subcareer as a fiction writer, and at the same time it was what kept him from writing the “big book” of political philosophy that his acolytes expected of him.

On the last page of Cruising Speed, he muses that the idea of quitting NR to join the academy and think deeper—about philosophy and theory—would be to solve a problem he doesn’t have. His real concern, he says, is to serve his readers while maintaining a constant rate of motion, and without getting bored: “How will I satisfy them, who listen to me today, tomorrow? Hell, how will I satisfy myself tomorrow, satisfying myself so imperfectly, which is not to say insufficiently, today; at cruising speed?”

More is revealed in these lines than in the entirety of Buckley’s Paris Review interview. There is anxiety beneath the amusing, protective convolutions of his syntax and the aftersound of the Sanctuary’s dance floor. It’s the anxiety of a writer at work, sure, but also of a man who worries what he might do if no one is watching.

News

Berita Teknologi

Berita Olahraga

Sports news

sports

Motivation

football prediction

technology

Berita Technologi

Berita Terkini

Tempat Wisata

News Flash

Football

Gaming

Game News

Gamers

Jasa Artikel

Jasa Backlink

Agen234

Agen234

Agen234

Resep

Download Film

Gaming center adalah sebuah tempat atau fasilitas yang menyediakan berbagai perangkat dan layanan untuk bermain video game, baik di PC, konsol, maupun mesin arcade. Gaming center ini bisa dikunjungi oleh siapa saja yang ingin bermain game secara individu atau bersama teman-teman. Beberapa gaming center juga sering digunakan sebagai lokasi turnamen game atau esports.