All photographs courtesy of the author.

One Easter Sunday, I attended a screening of the film Jesus Christ Superstar put on by my friend at the Brooklyn, New York, office of the well-respected literary magazine where she worked. There were about eight people there. All appeared to be treating the event as a substitute for church service: something they felt obliged to do. A French and comparative literature Ph.D. student made a point to tell me that he did not “get” musicals and was not expecting much from the film. He told me this, I think, because he knew I occasionally write theater reviews, attend Broadway musicals, and generally engage with the medium in a way that most people who pursue advanced degrees in French—and socialize at the offices of well-respected literary magazines on warm Sundays in April—do not. In the exchange that followed, I was able to ascertain that the real scourge for him was not movie musicals, which at least fit into a larger framework of film history, but the Broadway shows that are their frequent source material. It was a problem, he said, of overblown emotion. It was not relatable. I did not mount the exhaustive defense that he maybe thought I would. But I did ask him if he enjoyed going to the opera.

“Of course,” he said.

My own interest in the genre should not be overstated. Most Broadway musicals I have seen courtesy of comped tickets or evenings out with my parents. All those I’ve attended of my own volition have been written in some capacity by Stephen Sondheim, who is about as intellectually prudent a favorite as one can have while still being wearily unoriginal. Still, within my milieu, it doesn’t take much to be considered a “musicals person.” I wasn’t sure I was. But I found it odd that in a world where art and fashion and literature commingled with ease, musicals remained an object of scorn.

1. Ragtime

First there is a little boy tinkling on the piano, for whom the audience claps the way all audiences clap for little boys. Soon there is Everyone, a mob of people filling the cramped Lincoln Center stage from end to end, introducing themselves in the declarative third person (“Father was well off. Very well off”), before bellowing the choruses in unison. There is a phenomenon in choral singing that the musicologist MacKenzie Cadenhead calls “the phantom note,” when perfect harmony creates the illusion of a note that is octaves above the rest. Ragtime seems to be in continual pursuit of this note and of the collective hallucination that enables it. Indeed, the entire show is a mainlining of human pathos, each song a moment of moral reckoning whose power would be enough to close the curtain of any other show. Its effect is like highlighting every passage in a book. A thundering duet between the two Black protagonists, Coalhouse and Sarah, to their unborn baby leads to a fiery speech about textile-worker strikes by Emma Goldman, followed by the moment when the impoverished immigrant Tateh is about to send his daughter away to foster care. All this even before Sarah is murdered by the Secret Service. Then on to act 2.

It is not difficult to imagine why this production seemed an appealing candidate for a revival, first last fall at City Center Encores!, and then on its transfer to Broadway this past October. An adaptation of E. L. Doctorow’s titular novel, Ragtime has grandiose themes: race, class, political violence in American society at the turn of the twentieth century. Real-life figures like Goldman, Booker T. Washington, and Harry Houdini punctuate a story about the intersecting lives of people in New York: WASPs in New Rochelle, Black musicians in Harlem, and Latvian Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side. It presents a tempered patriotism, one unafraid of facing up to our country’s original sins. Tateh endures humiliating poverty and scorn while trying to make a life for himself as a silhouette artist on the Lower East Side. The occasional aside from Goldman suggests that perhaps the playwright Terrence McNally understands something of the systemic nature of the way this country treats its poor. But musicals are ultimately individualistic. So I found myself in quiet disbelief as the audience erupted into rapturous applause when Tateh invents the moving picture book that, by the beginning of act 2, has made him a wealthy director of early motion pictures. They applauded even harder for the show’s ending, when newly liberated housewife Mother and Tateh marry to form a blended family with the orphaned child of Sarah and Coalhouse (who has by now also been killed). The show has too much affection for its characters to make examples out of them, so even though Tateh may have become a bit impatient as a rich man, he still possesses the same kind heart. Ragtime may have a troubling, complex portrait of American society in its sights, but its adherence to our uniquely American mode of storytelling prevents us from feeling any true despair.

During the course of writing this piece, a friend and I went for a drink at the Townhouse, a handsome piano bar in the East Fifties that functions as a sort of after-hours nerve center for gay fans of Broadway. That night there happened to be a holiday party for OutPro, an LGBTQ professional networking association. We blended in well enough that we were approached several times to be, I suppose, networked. I struck up a conversation with one twenty-six-year-old accountant whose name tag indicated that he worked in the finance sector. I mentioned I was writing a piece on Broadway musicals, and right away I could tell he and I inhabited very different worlds; that in his, it was impossible to imagine somebody who hated musicals, all musicals. When pressed for an example, I mentioned Hamilton and the way it has begun to resemble an outdated remnant of the toothlessly progressive, feel-good liberalism of the Obama era. He stared at me blankly and finally asked, “Are you, like, a socialist or something?”

In the years since the gargantuan success of Hamilton and an industry-wide reckoning, post–George Floyd protests, Broadway productions have leaned in to liberal identity politics as their state ideology, favoring “message musicals” (like the women’s suffrage show Suffs) and casting stunts (an all-female 1776) that marry liberal identity politics with the genre’s emotional sincerity. “The earnestness of a civics lesson that New York Times critic Ben Brantley decried in Ragtime’s original 1998 production has been “imbued with a present-tense sense of civic necessity,” according to the same publication’s review of the revival. “Civic necessity” certainly describes the resurgent patriotism of liberals under Trump, a self-aware flagellation that nonetheless sounds a final note of triumph, or at least hope, for the American Project. It has even become a tradition for losing Democratic candidates to lick their wounds at Broadway shows, where they receive a standing ovation from a sympathetic crowd (Hillary Clinton at Sunset Boulevard); or deliver an inspirational speech backstage (Kamala Harris at A Wonderful World: The Louis Armstrong Musical); or pose for photos with the celebrity cast (Joe Biden at Othello).

While my boyfriend, M., rolled a cigarette during intermission, we talked about how unsettling it was to see a towering figure like Emma Goldman reduced to a kind of Jiminy Cricket resting on the shoulder of the show’s consciousness. When I told him the actress playing her also wrote Suffs, which was produced by Hillary Clinton, of all people, it seemed to encapsulate everything he dislikes about Broadway. I’d been hesitant to bring him, worried my interest might reveal something trite and sentimental about myself. Our relationship was then at what felt like a low point. We were avoiding a conversation about the future and what we wanted out of it. Under that tension, a musical can seem like an unnecessary escalation of the stakes. Musicals are intrusions on the detachment of spectatorship. They do not wait for you to figure out how you feel; they come right up in your face and tell you.

2. The Queen of Versailles

If you don’t watch YouTube reviewers or read the message boards, you may not know that the musical you are watching is the most reviled production of 2025. That was the case when S. and I attended a performance of The Queen of Versailles in mid-November 2025, and the show shortly thereafter announced its premature closing date of January 4, 2026, before abruptly moving it up to December 21. We knew something was wrong—it had not been very difficult to get cheap rush tickets that morning.

The Queen of Versailles is an adaptation of a 2012 documentary of the same name that shows the efforts of Jackie Siegel and her husband, David Siegel, CEO of the predatory time-share firm Westgate Resorts, to build the largest home in America. Touted as the reunion of Wicked composer Stephen Schwartz and Kristen Chenoweth, the original Glinda, and timed to open with the release of the second Wicked movie, it was instead met with scorn for its sympathetic portrayal of an avid Republican and literal avatar of American greed.

The musical, too, is riven with tension between its desire to humanize Jackie Siegel and to critique the bottomless consumption that animates her. Throughout the show, I kept looking at the row of women behind us for some clue as to how I was supposed to feel. Was I supposed to be happy when her husband promises to build her a replica of Versailles? Or sad when the 2008 financial crash halts construction on their monstrosity?

“It was like watching German theater,” S. said after the show ended. It is a complete pastiche of affect, carelessly tossing aside the earned emotion of one scene in favor of a punch line or a descent into the maudlin in the next. The show makes the uncanny but inevitable decision to include the real-world death of Jackie’s eldest daughter by overdose by way of an uplifting ballad during which Chenoweth wanders alone through her dead daughter’s bedroom. Having seemingly realized that her own shallow lifestyle contributed to her daughter’s low self-esteem, she resolves that “I’ve got to change, I’m going to change.” Only, by the next scene, she’s back to building the damn house! In fact, she is still building it to this day. The musical wants the house to be a metaphor for greed and for her search for “home,” without realizing how poorly those two things work together. But the conflation is also kind of brilliant, revealing a deep black cynicism that threatens to say something new about the hollowness of empowerment narratives in general. So of course no one wants to see it.

In September of 2025, the New York Times reported that, of the forty-six Broadway musicals that have opened since the pandemic, only three have been profitable. The economic model that Broadway is premised on is collapsing in real time from the skyrocketing costs of putting on a show. Perhaps the fate of the musical will be that of opera, a niche art form propped up by donors and attended only by enthusiasts. To tout the virtues of “populist forms of art” feels beside the point, but a strange, ugly piece of art like this one is possible only at the scale of a Broadway musical, and only when it chafes against the conventions of public taste in a way that more specialized or rarefied forms of art cannot. Yoked as they are to universal themes like community or patriotism, Broadway musicals are the public sculptures of the performing arts.

3. Chess

I went back to the Townhouse with M. on a night when the piano player happened to be hosting an impromptu trivia contest. Upon hearing the question of who was the only actress ever to reject her Tony nomination, I found myself blurting out, correctly, “Julie Andrews!” This won me nothing but a look of disbelief on M.’s face.

I am six years older than M.—nothing drastic, but enough that I sometimes worry I might appear to him like a sexless old queen, blathering in a raspy trill about Bette Davis movies, or which incarnation of Mama Rose was my favorite.Thirty-three years ago, a serial killer known as the Last Call Killer had stalked this same bar until the wee hours of the morning, taking lonely, drunken gay men home and dismembering them, before scattering their body parts across various New Jersey rest stops. Some of the men there seemed capable of murder when the slick young things they’d been seducing invariably lost interest.

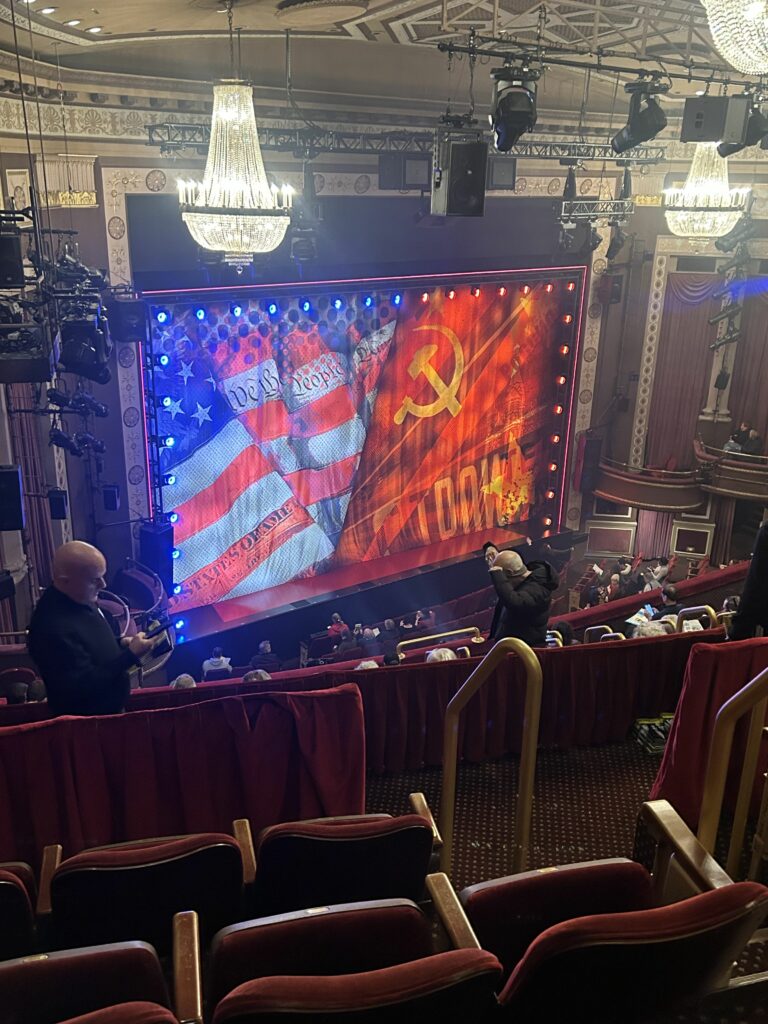

M. did not accompany me to any more shows. Like riding a roller coaster or seeing a horror movie alone, attending a musical by yourself is unseemly. But I really wanted to see Chess, the original musical by ABBA’s Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus, and the cheapest tickets were eighty-nine dollars. So I was seated alone in the very back of the mezzanine section of the Imperial Theatre, next to two well-dressed British men who smelled sharply of hotel bodywash. Its story line—a Cold War love triangle between a brash American chess player, his morose Soviet counterpart, and the Hungarian American migrant who loves them both—is notoriously convoluted. This revival also featured what I have always found to be a curious attribute of the Broadway musical: a revised book. Unlike a play, which is generally considered unchangeable, or a musical’s songs, which are likewise sacrosanct, the story, the actual dialogue and framing, seem to be open to all manner of editing, cutting, tweaking, and rewriting. In this instance, Empire co-creator Danny Strong imposed an awkward metanarrator character who constantly undercuts the story’s drama by reminding us that this show was written in 1984, apologizing for its datedness, and, lest we find it hard to relate, peppering his narration with hackish jokes about Donald Trump and RFK Jr. (Perhaps the producers were hoping for a backstage visit from Gavin Newsom.)

But Chess does have all the hallmarks of ABBA’s greatest songs—the layered harmonies, the pulsating, addictive choruses. It seems tautological to say that people come to musicals for the music, but it was a revelation to realize that the audience around me did not give a shit about the story that was unfolding. They had seen Glee. They wanted Lea Michele. “You’ve got to give it to her,” one of the British men said after she finished her centerpiece number, “Someone Else’s Story,” a crescendoing ballad that Michele’s character sings to her younger self. Audiences share an almost reflexive instinct to applaud loud singing. Ragtime, seemingly capitalizing on this impulse, consists almost entirely of belting. Inversely, the only moments of clarity in The Queen of Versailles’s muddled narrative are when Kristin Chenoweth clears the stage to coloratura her way to F above high C.

Because high notes almost always occur during what’s known as character songs (as opposed to action songs, which drive the plot), when someone onstage reveals their inner feelings, they express a unity of form and content, an emotional directness that can be startling if you are not accustomed to excavating your own feelings in so stentorian a manner. Characters sing to the audience the way we talk to ourselves, or are afraid to talk to ourselves. What the more refined among us often decry as “cringe” in theater kids is exactly this porousness between feeling and expression. Kristin Chenoweth walks around her dead daughter’s bedroom and declares, “I’ve got to change. I’m going to change.” Lea Michele comes to the realization that “I don’t see a reason to be lonely. I should take my chances further down the line.”

The first musical I saw was Jesus Christ Superstar, in a community production at a small opera house in Derry, New Hampshire, when I was twelve. What followed was a six-month period of religious fervor, during which I wore a cross necklace every day and believed I could feel the presence of God when I sat on a specific rock in my front yard. What had actually happened was that I had found a form of expression that matched the intensity of my preadolescent yearnings. Pop songs can be full of longing, but they are frequently addressed to a lover: I will always love you. In the central ballad from Jesus Christ Superstar, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” Mary does not convey her feelings to Jesus directly (who would dare?), but to herself, while he is sleeping. What musicals reveal to us is that our diaristic musings and private thoughts might not sound as sophisticated as we imagine.

![]()

4. Mamma Mia!

As a finale, I treated myself to a middle orchestra seat at Mamma Mia! When I was purchasing my ticket, the TodayTix app offered me a cheaper seat, closer to the stage. It wasn’t until I arrived at the Winter Garden Theatre that I realized I was in the first row.

Mamma Mia’s original sin, as is true of all jukebox musicals, is that it substitutes the well-established conventions of musical theater for a surge of adrenaline fueled by recognition—I know this song. Whereas in its ideal form, a musical seamlessly weaves together song and narrative, Mamma Mia! reverse-engineers its paternity-mystery story line (allegedly ripped off from the 1968 film Buona Sera, Mrs. Campbell). As a result, some songs just don’t fit in anywhere, hence the added detail that the main characters were all in a band together in the late 1970s. The show alternates between diegetic and non-diegetic songs, meaning that sometimes the characters are meant to be performing them in the story and sometimes they are singing in the abstract emotional space between stage and audience. This is not uncommon in traditional musicals about show business, but the diegetic songs are usually not meant to register as emotional beats.

But because ABBA songs are all self-contained, the moments when the characters are singing just for fun can have surprising resonance. My sole tears of the evening came not during the expected emotional climax of “The Winner Takes It All,” but from the throwaway opening lines of the comparatively lighthearted “Super Trouper”: “I was sick and tired of everything when I called you last night from Glasgow.” I was brought back to the period that had precipitated all this trouble with M., to phone calls expected and delayed or never received. Often the narratives I find most affecting are not the ones that mirror my own experience but those that show me what I lack. The context in which the song is sung—at a bachelorette party—has nothing to do with me. But I don’t think I would have cried had I been listening to the ABBA version alone at home. The French Ph.D. student’s complaint—that the scale of emotion in musicals is too great to be relatable—is a common criticism of the genre. But it is exactly this dissonance that reveals the impossibility of our own desires, or our unwillingness to pursue them. The scale of our emotions often makes them difficult to relate to.

Writer Jill Dolan uses the term performative utopias to describe “small but profound moments” in theater that reveal “what the world might be like if every moment of our lives were as emotionally voluminous, generous, aesthetically striking, and intersubjectively intense.” What I find most reassuring about this concept is its inverse implication of failure—the idea that most of theater does not succeed in achieving these profound moments. Sitting in the front row of Mamma Mia!, I noticed backup vocals when the actors’ mouths weren’t moving. The show uses recorded vocals to better achieve the familiar ABBA sound. I could also see into the wings, where I witnessed the detailed preparation of a sight gag involving a wedding dress that did not land with the audience whatsoever. The soufflé collapsed in front of me, and I saw the musical for the barest definition of what a musical is: a bunch of people mincing about onstage. Most musicals do not succeed, and not solely in the financial sense. It is incredibly hard to create a great one, and even then success is temporary; a musical production is not fixed in place the way an old masters painting is, or a film, or even a play, with the often-litigious estates of famous playwrights there to keep every sentence and pause in place. Even Dolan’s configuration is a little too precious for my taste; what keeps me interested in Broadway musicals is not just the possibility that one might lapse into an unexpected moment of transcendence but that they so frequently do not even approach it. It is an art form condemned to failure because it runs along the live wire of sentimentality, because it cannot hide behind a fog of interpretation.

M. and I finally find a time to talk, a few days before Thanksgiving. None of the doom I’ve anticipated come to pass. Periodically in our lives we are called upon to say, with the utmost sincerity, something as insipid as, I’ve got to change. I’m going to change.

Kevin Champoux is a writer in New York. His work has appeared in Frieze, Notebook, Document Journal, and other publications.

News

Berita Teknologi

Berita Olahraga

Sports news

sports

Motivation

football prediction

technology

Berita Technologi

Berita Terkini

Tempat Wisata

News Flash

Football

Gaming

Game News

Gamers

Jasa Artikel

Jasa Backlink

Agen234

Agen234

Agen234

Resep

Download Film

Gaming center adalah sebuah tempat atau fasilitas yang menyediakan berbagai perangkat dan layanan untuk bermain video game, baik di PC, konsol, maupun mesin arcade. Gaming center ini bisa dikunjungi oleh siapa saja yang ingin bermain game secara individu atau bersama teman-teman. Beberapa gaming center juga sering digunakan sebagai lokasi turnamen game atau esports.